holoscience.com | The ELECTRIC UNIVERSE®

A sound cosmology for the 21st century

MORE IO CLOSEUPS

Jupiter’s Moon Io: a Flashback to Earth’s Volcanic Past

Excerpts From A NASA/JPL Press Release November 19, 1999

Jupiter’s fiery moon Io is providing scientists with a window on volcanic activity and colossal lava flows similar to those that raged on Earth eons ago, thanks to new pictures and data gathered by NASA’s Galileo spacecraft.

The sharp images of Io were taken on Oct. 11 during the closest-ever spacecraft flyby of the moon, when Galileo dipped to just 380 miles (611 kilometers) above the surface. The new data reveal that Io, the most volcanic body in the solar system, is even more active than previously suspected, with more than 100 erupting volcanoes.

“The latest flyby has shown us gigantic lava flows and lava lakes, and towering, collapsing mountains,” said Dr. Alfred McEwen of the University of Arizona, Tucson, a member of the Galileo imaging team. “Io makes Dante’s Inferno seem like another day in paradise.”

Judging by the NASA/JPL News headline, NASA’s eye on funding seems to be more acute than its eye for science. To paraphrase an old joke about a hammer and a screw – when all you have is a geologist, everything looks like a volcano. The evidence points ever more strongly to electric arcs creating the hot spots and surface features on Io. Nevertheless the report continues:

Ancient rocks on Earth and other rocky planets show evidence of immense volcanic eruptions. The last comparable lava eruption on Earth occurred 15 million years ago, and it’s been over 2 billion years since lava as hot as that found on Io (reaching 2,700 degrees Fahrenheit) flowed on Earth.

“No people were around to observe and document these past events,” said Dr. Torrence Johnson, Galileo project scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), Pasadena, CA. “Io is the next best thing to traveling back in time to Earth’s earlier years. It gives us an opportunity to watch, in action, phenomena long dead in the rest of the solar system.”

As predicted by the ELECTRIC UNIVERSE® model several years ago, Io is a living laboratory for electrical sculpting of planetary surfaces. As for such activity being long dead in the rest of the solar system, that presupposes an undisturbed planetary system over billions of years. An objective assessment of the discoveries of the space age show that dogma to be wishful thinking as the estimates of planetary surface ages are drastically revised downward.

The new data focus on three of Io’s most active volcanoes – Pele, Loki and Prometheus. The vent region of Pele has an intense high-temperature hot spot that is remarkably steady, unlike lava flows that erupt in pulses, spread out over large areas, and then cool over time. This leads scientists to hypothesize that there must be an extremely active lava lake at Pele that constantly exposes fresh lava. Galileo’s camera snapped a close-up picture showing part of the volcano glowing in the dark. Hot lava, at most a few minutes old, forms a thin, curving line more than six miles (10 kilometers) long and up to 150 feet (50 meters) wide. Scientists believe this line is glowing liquid lava exposed as the solidifying crust breaks up along the caldera’s walls. This is similar to the behavior of active lava lakes in Hawaii, although Pele’s lava lake is a hundred times larger.

The intensely hot spot of Pele is visible in daylight. Its visibility and steady brightness is understandable if it is a hot spot of an electric arc. It does not require another ad hoc condition of lava in addition to its extreme temperature. The necklace of bright spots glowing in the dark fit the cathode spots model of the electric arc better than a line of exposed lava. The result would be a crater chain like a large version of those seen in the earlier closeup of Io and also in the latest image seen below. Crater chains are ubiquitous on solid surfaces throughout the solar system, from asteroids and the tiny moon of Mars (Phobos) to the Moon, Venus and Mars. They are not well explained by either internal geological forces or by external impact events.

The intensely hot spot of Pele is visible in daylight. Its visibility and steady brightness is understandable if it is a hot spot of an electric arc. It does not require another ad hoc condition of lava in addition to its extreme temperature. The necklace of bright spots glowing in the dark fit the cathode spots model of the electric arc better than a line of exposed lava. The result would be a crater chain like a large version of those seen in the earlier closeup of Io and also in the latest image seen below. Crater chains are ubiquitous on solid surfaces throughout the solar system, from asteroids and the tiny moon of Mars (Phobos) to the Moon, Venus and Mars. They are not well explained by either internal geological forces or by external impact events.

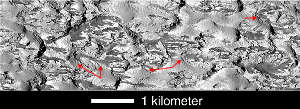

The image below is a closeup of “a degraded mountain” and shows “a lumpy landscape”. The caption released with the image reads: “Curiously, the variation in brightness between the dark and light areas within this image is the greatest seen to date on Io. Galileo scientists are continuing to investigate the processes that produce this puzzling surface”.

The dark areas seem consistently lower and flatter than the lumpy bright areas. This also fits with the view that the dark “volcanic flows” seen elsewhere are exposed sub-surface that has been melted and possibly chemically altered as a result of an impinging electric arc. Overlying material has been “spark machined” into space in the form of cathode jets (read “volcanic plumes” in conventional speak) at some earlier time. A feature of spark machining is circular pitting of the surface and a flat floor of the pits. Notice the tendency for circular scalloping of the edges of the dark material and its flatness. There also appear to be several small chains of circular pits. They, too, are a feature of cathode scarring and were seen in the first closeup of an Io “lava flow”.

The image has been slightly computer enhanced. The arrows point to some of the crater chains.

Mountains on Io are much taller than Earth’s largest mountains, towering up to 52,000 feet (16 kilometers) high. Paradoxically, they do not appear to be volcanoes. Scientists are not sure how the mountains form, but new Galileo images provide a fascinating picture of how they die. Concentric ridges covering the mountains and surrounding plateaus offer evidence that the mountains generate huge landslides as they collapse under the force of gravity. The ridges bear a striking resemblance to the rugged terrain surrounding giant Olympus Mons on Mars.

The resemblance is likely to be due to the fact that Olympus Mons itself is not a volcano but one of the largest anodic electrical scars yet discovered in the solar system. Such high mountains are formed by gargantuan electrical forces. Some of the concentric features are similar to those found on lightning arrestors after a lightning strike.

Image Credits: NASA/JPL

New Io images taken by the spacecraft are available at: http://www.jpl.nasa.gov/pictures/io [dead link 2021]